Nowadays, it’s obvious that the South doesn’t have a monopoly on great Southern food. Brooklynites can feast on country-fried steak and hot meatloaf sandwiches at The Brooklyn Star, and at San Francisco’s Boxing Room, the chefs make fried gator, crawfish étouffée, and rabbit and cornmeal dumplings to great acclaim.

What, then, makes Southern food so Southern if you’re eating it somewhere else?

For Chef Sean Brock, it has to do with feeling. “Southern food is about a particular emotion, and that could happen anywhere,” he said.

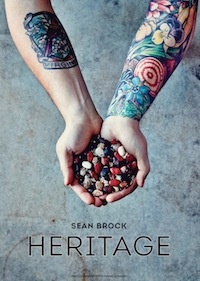

Brock knows plenty about Southern food. He grew up in Appalachia and now lives in Charleston, South Carolina, where he’s the chef of award-winning restaurants McCrady’s, Husk, and Minero. He also won the James Beard Award for Best Chef Southeast in 2010, starred in the Emmy-winning PBS show Mind of a Chef, and is now a New York Times best-selling author thanks to his first cookbook, Heritage, published in 2014.

For a firmer definition of Southern food, we spoke not just to Brock but also to Michael Galen, a chef serving Southern specialties well outside of the South at Chicago's Carriage House. Their combined insights gave us these three key tenets of Southern cooking.

“Southern” cuisine isn’t just one style. It’s more like 50.

To understand Southern cooking, Brock said, you need to understand how “insanely diverse the South is, and how many micro-cuisines it has. It’s not just one cuisine, it’s 50.” And each of those 50 styles is tied to a locale. A map of the regional South would have blurry borders that criss-cross different states, drawn by farming trends. “Each area has its own flavor based on its history, geography, culture, and most importantly, its agricultural history,” said Brock.

One of those many areas is the lowcountry, and lowcountry cuisine is Carriage House’s specialty. Chef Michael Galen honors the region—South Carolina and coastal Georgia—by blending tradition with innovation. “Many dishes are direct interpretations of traditional recipes dating back over 200 years,” he said. “The rest of the menu focuses on keeping the essence of the cuisine but letting creativity hold center stage.”

With so many Southern regions and micro-cuisines, there’s also bound to be some overlap. Galen noted that lowcountry cuisine strongly parallels with Cajun cooking, thanks to its focus on fresh seafood (think Frogmore Stew, she-crab soup, and Hoppin’ John).

In fact, saying that there are 50 Southern micro-cuisines might be lowballing it. As Kim Severson wrote in Garden & Gun: “Southern food is hundreds of micro-cuisines, from the rice, grits, and shrimp of the Lowcountry to the chocolate gravy of the Ozarks to the trout amandine of New Orleans. We are the Italy of America.”

Where you’re from doesn’t matter. Where your ingredients are from does.

“Treating your ingredients with respect is the most important [part of] achieving a successful representation of a cuisine,” said Galen. At Carriage House, he meticulously sources many of his ingredients—the grits in particular. “We source them directly from Geechie Boy Mill, a family-operated gristmill in Edisto Island, South Carolina.”

Brock echoed Galen, saying that “Good cooking involves a little work sometimes. Once you put the work in, you'll be rewarded with amazing food.” He noted that a large majority of the ingredients needed for his cookbook can be bought from Anson Mills, a company whose grains reflect the staples of South Carolina’s Antebellum cuisine.

The secret ingredient is always soul.

Ultimately, Southern cooking depends on your state of mind just as much as it does on your pantry. At least, that’s the case for Brock. His favorite dish in Heritage is a “deceptively simple” one that’s close to his heart: the cracklin’ cornbread. “[Cornbread is] on the table every day in the South, and it’s very personal to every family,” he said. He shared his recipe with us (you can follow it below), and recommended the cornbread as a beginner’s dish for any aspiring Southern cook.

“While I believe that it's the ingredients that play a major role in the flavor of a cuisine, it's also the soul and the care you put into it,” Brock said. And again, he added: “That could happen anywhere.”

Cracklin' Cornbread Recipe

Excerpted from Heritage by Sean Brock (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2014.

Makes one 9-inch round loaf

My favorite ball cap, made by Billy Reid, has a patch on the front that reads “Make Cornbread, Not War.” I’m drawn to it because cornbread is a sacred thing in the South, almost a way of life. But cornbread, like barbeque, can be the subject of great debate among Southerners. Flour or no flour? Sugar or no sugar? Is there an egg involved? All are legitimate questions.

When we opened Husk, I knew that we had to serve cornbread. I also knew that there is a lot of bad cornbread out there in the restaurant world, usually cooked before service and reheated, or held in a warming drawer. I won’t touch that stuff because, yes, I am a cornbread snob. My cornbread has no flour and no sugar. It has the tang of good buttermilk and a little smoke from Allan Benton’s smokehouse bacon. You’ve got to cook the cornbread just before you want to eat it, in a black skillet, with plenty of smoking-hot grease. That is the secret to a golden, crunchy exterior. Use very high heat, so hot that the batter screeches as it hits the pan. It’s a deceptively simple process, but practice makes perfect, which may be why many Southerners make cornbread every single day.

- 4 ounces bacon, preferably Benton’s

- 2 cups cornmeal, preferably Anson Mills Antebellum Coarse Yellow Cornmeal

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

- ½ teaspoon baking soda

- ½ teaspoon baking powder

- 1½ cups whole-milk buttermilk

- 1 large egg, lightly beaten

1. Preheat the oven to 450°F. Put a 9-inch cast-iron skillet in the oven to preheat for at least 10 minutes.

2. Run the bacon through a meat grinder or very finely mince it. Put the bacon in a skillet large enough to hold it in one layer and cook over medium-low heat, stirring frequently so that it doesn’t burn, until the fat is rendered and the bits of bacon are crispy, 4 to 5 minutes. Remove the bits of bacon to a paper towel to drain, reserving the fat. You need 5 tablespoons bacon fat for this recipe.

3. Combine the cornmeal, salt, baking soda, baking powder, and bits of bacon in a medium bowl. Reserve 1 tablespoon of the bacon fat and combine the remaining 4 tablespoons fat, the buttermilk, and egg in a small bowl. Stir the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients just to combine; do not overmix.

4. Move the skillet from the oven to the stove, placing it over high heat. Add the reserved tablespoon of bacon fat and swirl to coat the skillet. Pour in the batter, distributing it evenly. It should sizzle.

5. Bake the cornbread for about 20 minutes, until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean. Serve warm from the skillet.

Heritage photographs by Peter Frank Edwards. Top photograph by Groupon.

Bite into classic comfort foods: